Following a residency at MITsp 2020 in Brazil, artist & producer Sarah Hunter reflects on how complex ideas are communicated between people, languages and cultures.

As with most Quarantine processes, we began our month-long residency at MITsp by eating together. We welcomed our new collaborators with homemade lemon drizzle cake, scones with cream and jam, and breakfast tea with milk. They brought bananada (banana jam), açai smoothies, doce de leite, dragon fruit, and a kilo of brazil nuts. A delicious exchange of food and cultural stereotypes. Around the table with us were 12 Brazilian artists. For most, this was their first time meeting each other too. Aged from their early-twenties to mid-seventies, they brought a range of experience in choreography, writing, performing, filmmaking, journalism, architecture, design, taxi driving, hotel management…

With us too were Lucas, our producer from the festival, and Juli, our translator. The four of us from Quarantine (Kate Daley, Richard Gregory, Renny O’Shea and me) knew only basic words in Portuguese and while a few of the artists had good English, most spoke only a little and others none at all. This was my first experience of working with a group where we did not have a common language. I loved it. Since arriving home, I’ve been thinking about what it meant to spend four weeks in a state of translation – the richness and complexities of occupying the spaces that exist in the gaps between people, languages and cultures.

COMEÇOU

We began our residency, which was based at São Paulo Cultural Centre, with only a starting question and the idea to create an exhibition of people. The question was: who is visible and invisible in São Paulo today?

We discussed it at length. There was often disagreement. Of course. We were talking about a city with a population of more than 20 million people. Even for those speaking in the same language sometimes ideas did not translate easily. The experience of living there is not the same for everyone. We talked about the possibility of bringing people in from the city to be part of our exhibition; people who might not normally be visible in the cultural centre. We tried to work out who and why. The conversation returned often to the ethics and aesthetics of working with ‘real people’ as subjects. One of the artists posed the important question: who the hell are we? Fundamentally, this was a conversation about power. About the systems of representation (in politics, in art) that sustain (in)visibility for different kinds of people.

Having complex conversations through a translator takes a long time. It required us to find a new rhythm together. In contrast to the speed and noise of the city, this felt like a slowing down; which did not mean it was without energy. Conversations happened in fragments, a long burst of exchanges in one language and then a moment of waiting for those who had spoken as their words got relayed, and often responded to, in another. The act of listening felt different. Often, when the conversation was in Portuguese, I found myself letting sounds wash over me, giving attention instead to the patterns of speech, the tones of the voices, expressions on faces and gestures of bodies. It is amazing how much we can communicate and understand simply from watching some people speak while other people listen.

ÀS SEGUNDAS-FEIRAS ESTE LOCAL É FECHADO

One of my favourite words in Portuguese is bambolê. I like the way the sounds of the word move up and down like a wave. In English it means ‘hula hoop’. Juli translated it for us during a conversation about an exercise that school children do where a hoop is thrown on the ground to select a random sample of an area for closer inspection.

At many points in the process we threw a metaphorical bambolê around the cultural centre, our shared reference point in this city, to test what it might tell us about visibility or invisibility in the rest of São Paulo. At first, it seemed like it might not translate: the people in this place were too similar; there were too many people missing. We returned to look more closely.

The cultural centre is an extraordinary building with open architecture that makes it possible to observe all of the individuals and groups using the space at the same time. In a single session of people-watching you might see others: working, reading, eating lunch, meeting, drinking coffee, kissing, rehearsing, snoozing, thinking, writing, practicing an instrument, doing yoga, learning embroidery, browsing the galleries, playing chess, learning languages, or dancing – there was always dancing.

The central courtyard was where the dancing happened. At first glance it appeared to be a random collision of styles and music: a trio take it in turns to practice and instruct on the tango; a boy band perfect their latest pop routine; a young woman dances solo to hip-hop; a group of older dancers samba in time; and a couple perform an elaborate duet that involves the passing of a flag. But look again and you’ll get a small glimpse into an economic situation in this city: lots of dance schools rehearse here because they cannot afford to hire a space. Look again (and again and again) and you’ll notice that the kinds of dancing and types of people depend on the day of the week and time of the day. Look for longer and you’ll see that often the dancers echo what else is going on in the city: it’s almost Carnavale so samba, samba, samba; there is a Korean dance festival happening next week; there is going to be a takeover on Avenida Paulista for International Woman’s Day. Stop just looking and start to talk with some of the dancers and you will uncover more layers: the street dancers who rotate between the city’s cultural centres to maintain their claim on the best spots for breakdancing through persistence of presence; the teenager who dances here with friends while her grandmother waits (she brings her on her days off from work on the chemotherapy wards); the woman with the braids who does not get on with her family and dances here because she feels like she can be herself. (In)visibility exists in layers.

Across the centre it is the same. At the chess tables is a man who came to Brazil in 1975 with only $15 in his pocket. He was fleeing the revolution in Mozambique where they were killing white people. Slumped on a sofa is a man that recently moved here from Rio because São Paulo is where the money is. He has no friends yet in this city and comes here to feel less alone. In the community garden is a woman studying German. She has been to Germany and is desperate to go again; São Paulo has never felt like her home. On a bench are two young punks with a broken mobile phone. They feel invisible in this city because they live in a poor suburb on the margins. Sat on the floor in one of the gallery spaces are a kissing couple. They just met through a vegan dating app. Scribbling in her notebook at one of the free desks is a blue-haired woman who has coffee with her mum every single morning. Lying near the toilets across from the entrance is an older man who comes inside most days. He is married with two children; he has slept outside the cultural centre now for 16 years.

The city is here in this place because this place is here in this city. It’s not a representative sample, just a sample, the same as if we threw our metaphorical bambolê down in any other part of São Paulo. The nature of the layout and make up of cities means that in every location there will always be someone missing. But the politics, contradictions, chaos, hopes and fears of this city exist here in this place too – if you look closely and for long enough, you will find them in the spaces between people, waiting to be made visible.

PAPELÃO, TINTA E 250 SLOGANS: SINAIS DO NOSSO TEMPO*

*“‘Sinais’ is the literal translation for ‘signs’. In Portuguese, it means ‘signal’ (literally) and/or ‘indication, symptoms, hints, suggestions’. It doesn’t mean ‘posters’ though. The word for that would be ‘cartaz’, which doesn’t have the double meaning I believe you are looking for.”

In the final weekend of our residency we did a sharing of our process. It was presented in the gallery spaces on the top level of the cultural centre and on the ramps that run through the centre of the building, linking the different floors. We made lots of responses to and with this place and the individuals that occupy it: an exhibition of living people where members of the public could talk to the exhibits; filmed close-ups of 41 strangers; a gallery filled with people doing the things they usually do at the centre but with permission for the public to look more closely or join them; a relay interview where anyone could ask anyone anything about their life (one question only, no follow-ups); and the blueprint for the cultural centre painted large-scale onto the wall of the building by the architect in the our group: você está aqui.

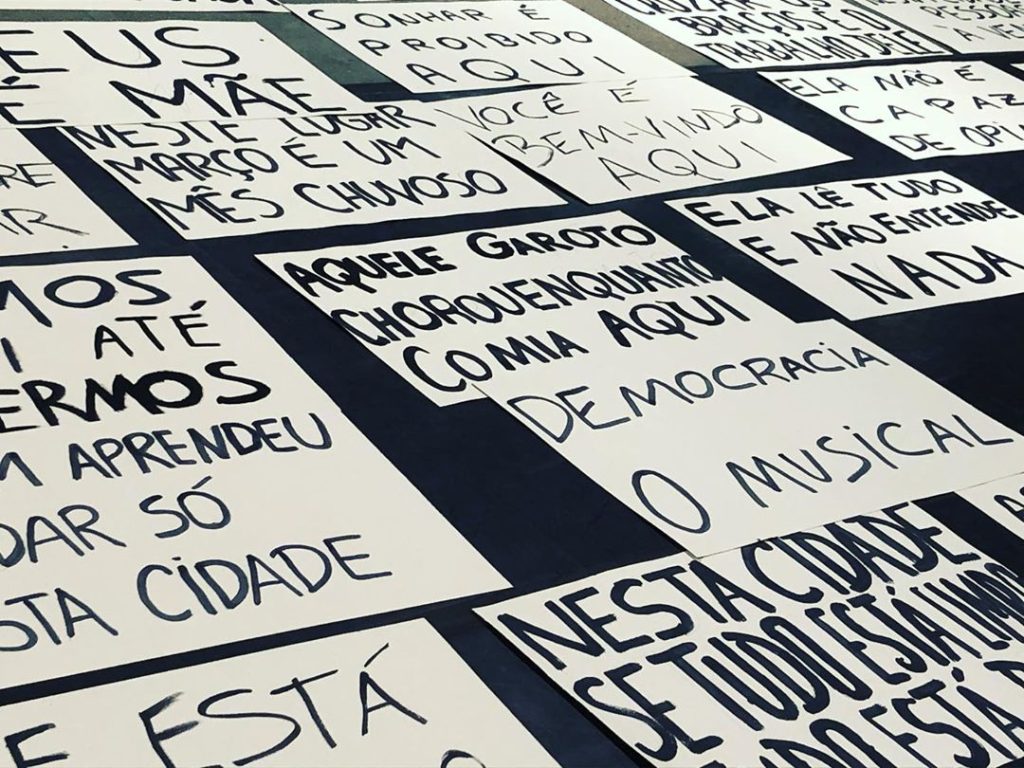

As part of this, we created a text to be turned into 250 signs. Grown from observations made by the group during our many people watching sessions and conversations, it was an attempt to represent in a series of slogans something of here, this place, this city. It was a mixture of the obvious, the very visible, and things that might go unnoticed or not otherwise be made public.

We translated the slogans back and forth between Portuguese and English, trying to make it possible for us all to understand how it was coming together as a whole. Literal translations, word for word, rarely sufficed, because phrases quickly lost their meaning (see * above, which was Juli’s note to me trying to find a way to communicate the double meaning of the English phrase ‘signs of the times’). Some slogans were beyond translation – references to politics, popular culture and idioms that made sense only in Portuguese.

The process of making the signs took several days and required a production line: one person writing the slogans in pencil and a group of others tracing over the lines of the words in black paint. Finished signs were laid out in the studio space to dry; so many of them they covered the entire floor. On the weekend of the performance, the signs were displayed in one of the gallery spaces, some stacked against the wall, others in piles. During the two-hour exhibition, the artists began to move these signs out into the rest of the building; walking with them or holding them up for people to see, before taping them on to the bannisters of the ramps. They were often joined by members of the public who, without instruction, sifted through the signs, chose a slogan and brought it into the space. Moved out of the gallery, the signs took on a life of their own, assuming new meaning depending on what or who they were placed beside. Over the course of the event, the centre was filled with these signs: a live curated text, changing all the time, here, in this place, in this city…

A comida aqui não é tão boa quanto a da mãe dela. Nesta cidade se tudo está limpo tudo está bem. Próxima estação: Paraíso. Menos de um ano até o Carnaval de 2021. Aqui existe uma mulher feita de mármore. A saída de emergência está sempre aberta. Neste lugar há muitas cadeiras, mas nenhuma decisão. Cruzar os braços é o trabalho dele. Alguém que aprendeu a andar sozinho nesta cidade. Democracia o musical. Pirralha! Ele paga por sexo nesta cidade. A gripe é a menor das nossas preocupações. Ele está esperando pelo namorado. De longe, ela se parece com a filha de alguém. Deus é mãe. Não é assim que se pronuncia o nome dela. Brenda, 976584321. O amigo invisível dele mora aqui. Aí vem outro discurso político. As paredes aqui estão sujas. Nesta cidade, revolução é dinheiro no bolso dela. Eles estão dormindo em um papelão. Eles votaram no Bolsonaro. Nós votamos no Bolsonaro. Segue o fluxo. Ela limpa os banheiros aqui uma vez por hora. Eles estão aqui para garantir que não violemos as regras. Eles passam o tempo aqui porque é grátis. Nesta cidade há muitas pessoas. Dançamos com nossos corpos juntos. Nesta cidade há muitos pássaros. “Uma cara de homossexual terrível”. O café aqui é forte. Ela tem dores de cabeça. Não há sabão nos banheiros. Cubra a boca quando tossir. Se eles vendessem caipirinhas aqui. Nesta cidade nunca neva. Não há crianças. Luz vermelha sangue. “Feliz” dia internacional das mulheres. Quem matou Marielle? Nesta cidade ela fez muitas tatuagens. Nesta cidade é difícil ver as estrelas. Às segundas-feiras este local é fechado.

The food here is not as good as his mum’s. In this city if everything is clean everything is fine. Next station: Paradise. Less than a year until Carnival 2021. Here there is a woman made of marble. The emergency exit is always open. In this place are many chairs but no decisions. Crossing his arms is his job. Someone who learned to walk alone in this city. Democracy the musical. Brat! He pays for sex in this city. In this city rich people eat six meals a day. Flu is the least of our worries. He is waiting for his boyfriend. From a distance she looks like someone’s daughter. Deus é mãe. That’s not how to pronounce her name. Brenda, 976584321. His invisible friend lives here. Here comes another political speech. The walls here are dirty. In this city revolution is money in her pocket. They are sleeping on cardboard. They voted for Bolsonaro. We voted for Bolsonaro. Segue o fluxo. She cleans the toilets here once an hour. They are here to make sure we don’t break the rules. They spend time here because it’s free. There are too many people in this city. We dance with our bodies close together. In this city there are many birds. “Uma cara de homossexual terrível”. The coffee here is strong. She gets headaches. There is no soap in the toilets. Cover your mouth when you cough. If only they sold caipirinhas here. In this city it never snows. There are no children. Blood red light. “Happy” international woman’s day. Who killed Marielle? In this city she got lots of tattoos. In this city it is hard to see the stars. On Mondays this place is closed.